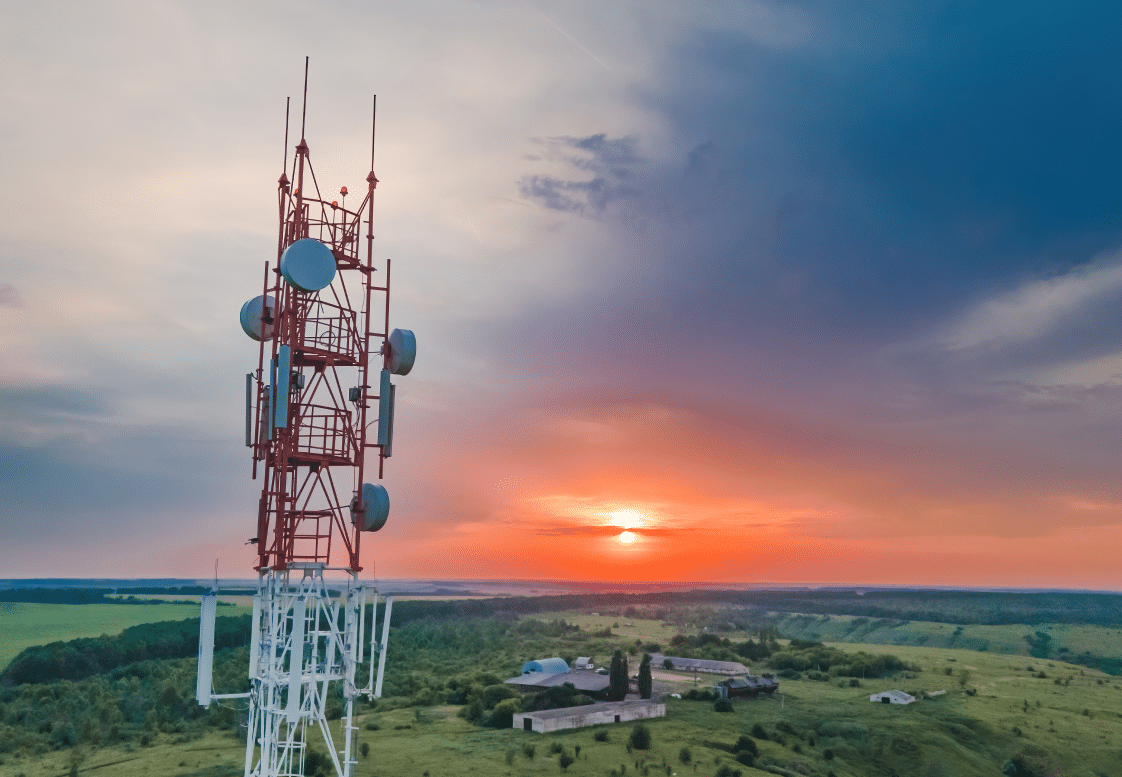

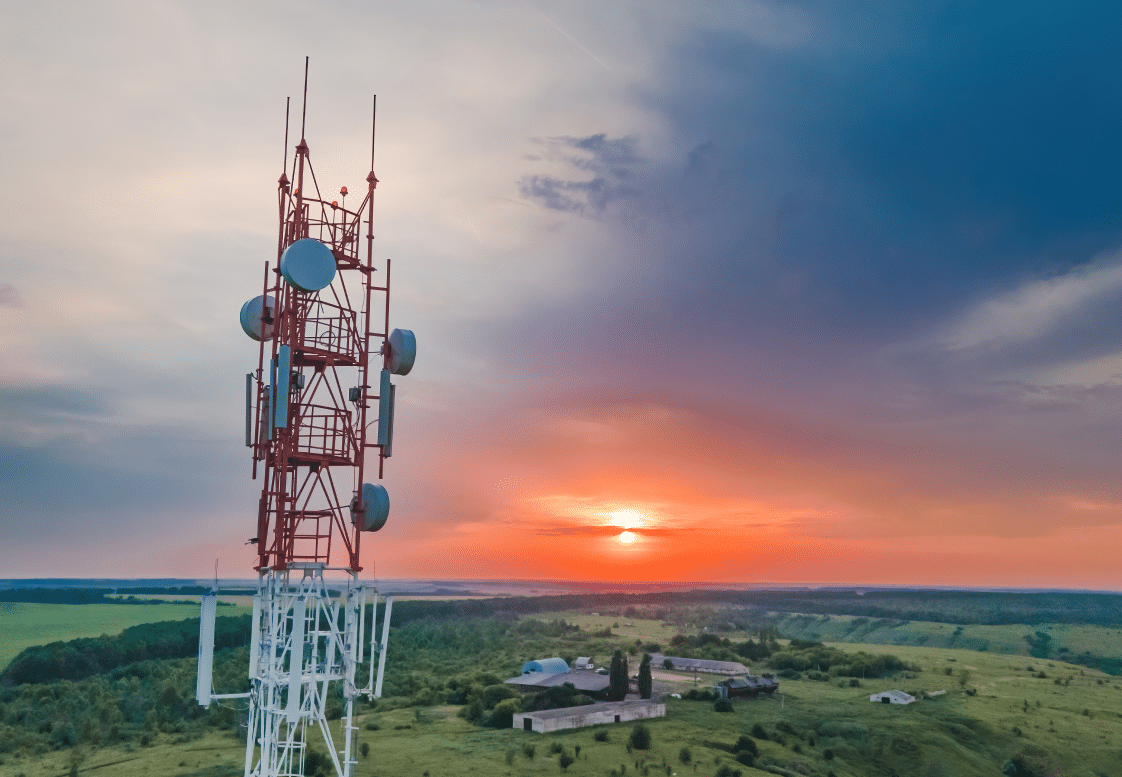

In a major boost to telecommunication infrastructure, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Saturday inaugurated BSNL’s ‘Swadeshi’ 4G stack, marking India’s entry into a coveted league of nations, such as Denmark, Sweden, South Korea, and China, which manufacture homegrown telecom equipment. In this context, let’s learn about the progression from generation one (1G) to the fifth, each generation of telecom technology, and understand what changed with each ‘G’ (generation).

Key Takeaways :

- Launched in the late 1970s in Japan, 1G was the first generation of mobile telecommunication technology that offered voice calls only. But it came with low sound quality, low coverage, and without any roaming support.

- The major leap for telecom tech of that time came in 1991 with the introduction of 2G. The analog signals of 1G became completely digital in the second generation.

- Apart from introducing the CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access) and GSM (Global System for Mobile Communication) concepts, it allowed users to roam and offered small data services like SMS and MMS at a maximum speed of around 50 kbps. While the focus was still on voice calling, data support was introduced.

- Mobile technology kept its date with generational leap every decade with the introduction of 3G services in 2001. It promised four times faster data transmission with access to mobile Internet. This is the generation that brought emails, navigational maps, video calling, web browsing and music to mobile phones

- High speed, high quality, high capacity voice and data services – that’s the promise that 4G brought with it around 2010. Standard 4G came with five to seven times faster speeds than 3G.

- Compared to 3G, a phone on a 4G network got quicker response to its requests (lower latency). This is what made our phones more like hand-held computing devices.

- 5G or fifth generation brought major upgrades in the long-term evolution (LTE) mobile broadband networks. 5G mainly works in 3 bands, namely low, mid and high frequency spectrum — all of which have their own uses as well as limitations.

- With increase in cellular bandwidth, blazing speed and low latency, 5G boosts the ‘Internet of Things’ by making it easy for several devices to connect to each other to communicate and to be controlled remotely.

- From generation one (1G) to the fifth, each generation of telecom technology has sought to change for the better the way humans interact with each other and the world around them. Notably, while technically not a functioning technology as of now, 6G has been conceived as a far superior technology promising internet speeds up to 100 times faster than 5G.

Bharat 6G Project

- India is gearing up to roll out high-speed 6G communication services by 2030 and has set up a Bharat 6G project to identify and fund research and deployment of the next-generation technology in the country, according to a vision document unveiled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in October last year.

- India’s 6G project will be implemented in two phases, and the government has also appointed an apex council to oversee the project and focus on issues such as standardization, identification of the spectrum for 6G usage, create an ecosystem for devices and systems, and figure out finances for research and development, among other things.

- While, technically, 6G does not exist today, it has been conceived as a far superior technology promising internet speeds up to 100 times faster than 5G.

- As per the vision document, 6G use cases will include remote-controlled factories, constantly communicating self-driven cars and smart wearables taking inputs directly from human senses. However, while 6G promises growth, it will simultaneously have to be balanced with sustainability since most 6G supporting communication devices will be battery-powered and can have a significant carbon footprint, the document said.

- The 6G project is proposed to be implemented in two phases: the first one from 2023 to 2025 and the second one from 2025 to 2030.

- In phase one, support will be provided to explorative ideas, risky pathways and proof-of-concept tests.

- Ideas and concepts that show promise and potential for acceptance by the global peer community will be adequately supported to develop them to completion, establish their use cases and benefits, and create implementational IPs and testbeds leading to commercialization as part of phase two.

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi formally launched 5G services in October 2022 and said at the time that India should be ready to launch 6G services in the next 10 years. As opposed to 5G, which at its peak can offer internet speeds up to 10 Gbps, 6G promises to offer ultra-low latency with speeds up to 1 Tbps.

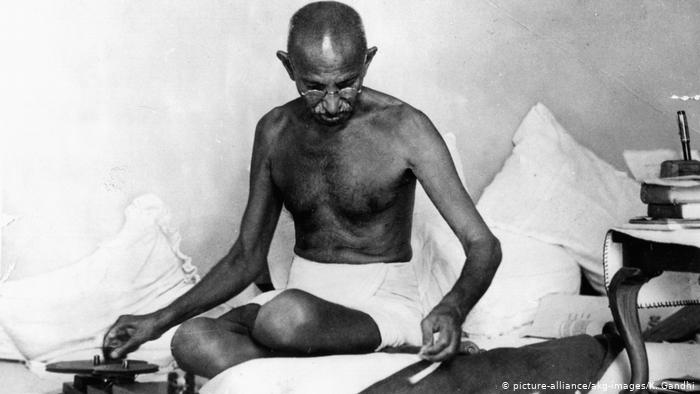

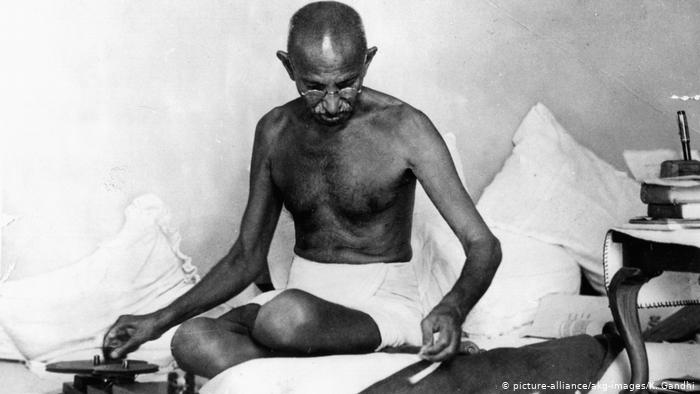

Mahatma Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj is perhaps his most well-known work, written in the form of a dialogue between an editor and his reader. Gandhi wrote this book in a very short duration of nine days between November 13 and 22, 1909, on board the ship Kildonan Castle on his return voyage to South Africa from London.

The dialogue unfolds through a series of questions and clarifications that the reader seeks from the editor about themes as diverse as civilisation, violence, passive resistance and swaraj, among many others. It is significant that Gandhi wrote this work first in Gujarati and later translated it into English himself.

The early and expatriate Gandhi

Hind Swaraj captures Gandhi’s early political thought on matters related to India’s colonial subjugation by the British. It was written some years before he assumed the leadership of the national movement. Gandhi returned to India in 1915 after spending two decades in South Africa. The book, therefore, represents his thinking before he went on to lead India’s national movement into what is called the ‘mass movement phase’. It also contains the perspective of an expatriate Indian, who is viewing the colonial situation of his homeland from a distance.

Prior to the mass movement phase, and especially in the early days of the establishment of the Indian National Congress, the national movement was characterised by polite petitioning that sought to redress the wrongs of British rule over India. These early nationalist stirrings did not come anywhere near a demand for the elimination of British rule and complete independence for India.

Petitioning of the kind that characterised the early Indian national movement was viewed as ‘derogatory’ in Hind Swaraj. The Indian national movement itself was led by many famous lawyers and barristers, and this professional tilt of the leadership is reflected in the nature of the national movement in its early days.

Hind Swaraj is itself very critical of the role of lawyers and barristers, not as individual professionals, but the larger structure of the profession, which in Gandhi’s view seeks to profit from the prolonging of disputes. Such a critical view assumes significance as Gandhi himself was a lawyer, admitted to the Inner Temple in London in 1888 and called to the Bar in 1891.

Similarly, Gandhi criticised the profession of modern medicine for its tendency to profit from the problems of ill health. The bleak view of law and medicine in Hind Swaraj is likened to Plato’s famous work Republic, where an ideal society governed by a philosopher-ruler makes the two professions redundant. Another point of similarity with Plato’s works is the adoption of the dialogue format.

Hind Swaraj is written in the immediate backdrop of the split within the Congress between moderates and extremists at the Surat session in 1907. It bears the imprint of this political rift, in addition to the Partition of Bengal in 1905. This shows that even though Gandhi had not arrived in India, he was following political events very closely.

Critique of modern civilization

Perhaps the most important theme of Hind Swaraj is its critique of modern civilization and the corrupting influence it has on the the moral fabric of society. Gandhi does not view British colonial expansion as emanating from any position of strength, but rather from weakness; as the British, he argues, had deviated from their own strengths. The major reason for this critique of modern civilization is because of its excessive reliance on machinery.

In line with arguments of this kind, mention is made of perhaps the most visible and spectacular aspect of British rule in India, which is the railways that, in Gandhi’s view, was disruptive of the social and economic equilibrium of the hinterland. Hind Swaraj is also critical of the rise of the big metropolis, as Gandhi views big urban concentrations such as Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai) as breeding grounds for moral decay.

Gandhi then posits that modern civilization is the “plague”, and contrasts it with the enduring values of Indian civilization. He feels that self-rule or swaraj could not be attained by adopting the ways of the British. Rather, it requires the recovery and revival of the simple, enduring qualities of Indian civilization. Here, Gandhi again contrasts the simple sustainability of the Indian village with the sprawl that modern cities have become.

Distinction between ‘soul force’ and ‘body force’

For Gandhi, the way to end British rule is through passive resistance, because violent resistance is morally wrong. A key theme of Hind Swaraj is the distinction made between ‘soul force’ and ‘body force’. Passive resistance involves a form of suffering of the self, which will bring about the desired change in a more enduring manner. We usually think of resistance as physical, mechanical, and external force exerted by the oppressed against their rulers, what Gandhi called ‘body force’.

His idea of passive resistance involved the internalization of suffering by the oppressed. The ‘soul force’ generated through this process of suffering has the potential to bring about more profound change, even in the heart of the oppressor, as it is connected to a larger struggle for truth or satyagraha.

The discussion of swaraj has a very philosophical basis to it. Swaraj or self-rule is not simply about forcing the British to leave India. In fact, Gandhi is very emphatic about not pursuing a swaraj where India becomes an imitation of the British. Rather, he emphasises the originality of self-rule, and goes on to argue that this cannot happen if the leaders of the national movement continue to think, write and speak in a colonially-imposed English. Hind Swaraj, thus, becomes one of the earliest works to advocate Hindi in the Devanagari script as a national language.